The Thames Foreshore in London is a very peculiar place. Running through one of the worlds greatest cities, one that boasts a half-million year prehistory, a two-thousand year history, and was until recently the capital of the largest empire the world ever saw, the Thames is peculiar not because other great cities don't have rivers. Most do. It's peculiarity resides in the fact that it is narrowly embanked but also tidal. And so on a big spring tide the river can rise to within a gnats cock of the top of the wall but at every low its ancient detritus laden bed is exposed and accessible to all.

|

| Spring high at Custom House |

But it's a long fall down. Let's put it this way. Unless my life depended on it, I would never use one of the vertical access ladders. Luckily there are less dangerous steps spaced at fairly regular intervals. That means that your average day tripper out on a hunt can go down, reasonably expect to find things old and unknown, and go home with a handful of bits and bobs to adorn the mantle-piece. It also means the seasoned mudlark may reasonably expect to find something every once in a while that is not only very old but fit for display in a museum case.

The discovery I made one sunny afternoon in May falls somewhere between those two polar extremes. Therefore it resides carefully stowed in my collection cabinet. Once in a while I get it out and look at it. I can't ever remember showing it to anyone.

| A chalk-rubble barge bed being laid at UDC Wharf, Chiswick on Easter Sunday, 1929. (MOL Collections) |

The Thames was once studded with barge beds. Wharves that dealt in bargeloads rather than shiploads required them so that the flat-bottomed vessels would land gently at low tide on level hard standing where unloading would commence. Otherwise they'd tilt the load precariously making already hard work harder for the stevedors. The find was made on one. Nothing unusual about that — many finds are.

Thames finds, and the majority made on the North Bank in the City (which except for the opening at Queenhithe Dock was once an unbroken chain of barge beds) often aren't as many believe they are, direct losses. Stuff dropped by people over the sides of boats or thrown into the water when broken or unfashionable. Most often they got there indirectly and derive from these long redundant and derelict constructions.

Erosion begins when water having breached the wooden revetment begins its levelling work and begins to claw back its original course. The channel once begun opens ever wider at each and every turn of the tide till eventually the entire bed is reduced to loose rubble and shifting shingle, its stark oaken bones the only reminder it ever existed. A whole barge bed can be made nothing in a decade.

Erosion begins when water having breached the wooden revetment begins its levelling work and begins to claw back its original course. The channel once begun opens ever wider at each and every turn of the tide till eventually the entire bed is reduced to loose rubble and shifting shingle, its stark oaken bones the only reminder it ever existed. A whole barge bed can be made nothing in a decade.

|

| A barge bed at a busy Victorian wharf |

They were made out of what was readily available nearby and the kind of stuff that others would otherwise have pay to have carted away. Compacted street sweepings, industrial and domestic rubbish and hearth tippings, demolition rubble and the spoil from new building foundation excavations (that in London will always cut through earlier layers and much older rubbish pits) and all kinds stuffs from all kinds of sources was piled in and rammed down hard. So much so that the beds are concreted throughout. All of this is very gradually loosened and freed by the very gentle but powerfully persuasive action of moving water.

The wood ash and fine coal dust is taken away in solution. The sand and gravel is washed here and there. The wood and the bone are light and are all taken elsewhere. The fragments of brick and stone, the shards of glass and pottery, are dense and heavy and remain behind. Amongst what's left will be bits and pieces of real interest and most of these are of metal often preserved so beautifully that they appear to have made the very day before.

The wood ash and fine coal dust is taken away in solution. The sand and gravel is washed here and there. The wood and the bone are light and are all taken elsewhere. The fragments of brick and stone, the shards of glass and pottery, are dense and heavy and remain behind. Amongst what's left will be bits and pieces of real interest and most of these are of metal often preserved so beautifully that they appear to have made the very day before.

However this find was made on top of the rammed rubble capping of a bed at Trig Stairs that at the time was fully intact. The revetment was whole and serious erosion had never taken place there and so the finds it contained were still locked inside.

How did it get to be there?

Well, I think that's quite an interesting question. To be on top I think it had to have been lost or thrown directly into the river, not dumped into a containing wooden frame along with a million and one other discarded things.

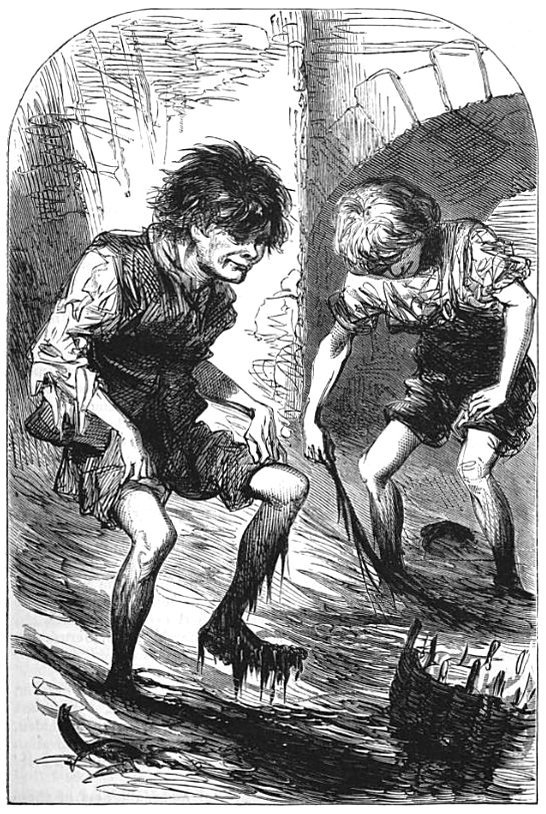

If so then its discovery was something of a miracle of chance, not because it hadn't been found by a modern day mudlark, but because in the past the Thames was scoured by daylight and lamplight by those with a rather more pressing and urgent need who weren't there to oik out a treasure but to eke out a living. And they'd hunt down every last valuable, saleable, useable, combustible (and God forbid, edible...) scrap they could find.

I always like to think of it as one of the many pretty trinkets from Fagin's lost treasure box. And it would have secured a poor mudlark's family food supply for a month, I'm sure. But they missed it. And so did everyone else for two long centuries.

And then one day I was picking over a sloping shingle bed that had always been rather good to me and when I'd finished with it began walking westward across the intervening barge bed to another favourite hotspot, when the faintest glimmer of old gold caught the corner of my eye.

It was a fragment of chain. At least I thought that's all it was until I picked it up when I realised it was attached to something beneath the gloopy mud. Gently teasing the chain I couldn't quite get beyond five inches before it stuck fast so I plunged my hand right in, scooped my hand beneath the lot and lifted as carefully as I could.

The whole fistful came out quite easily so I walked back to the shingle bank where squatting at the water's edge, I immersed the grey lump in the Thames, and there began the careful job of washing whatever the hell that chain was attached to, out.

The whole fistful came out quite easily so I walked back to the shingle bank where squatting at the water's edge, I immersed the grey lump in the Thames, and there began the careful job of washing whatever the hell that chain was attached to, out.

No comments:

Post a Comment